Excerpt from a story published on healthjournalism.org.

Athens, Ga., is a small city about 75 miles east of Atlanta. Older adults love its low cost of living, community-mindedness and proximity to a major urban area. What they don’t love, however, is the poor access to specialized senior health care.

Nearly 10 percent (11,830) of the city’s 120,000 residents are over age 65, but only three office-based geriatricians practice here.

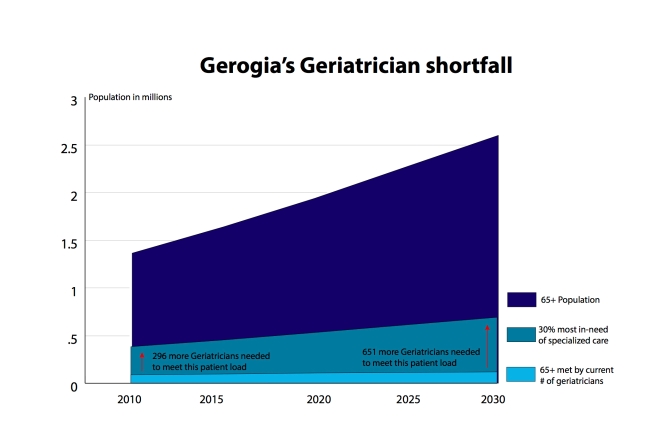

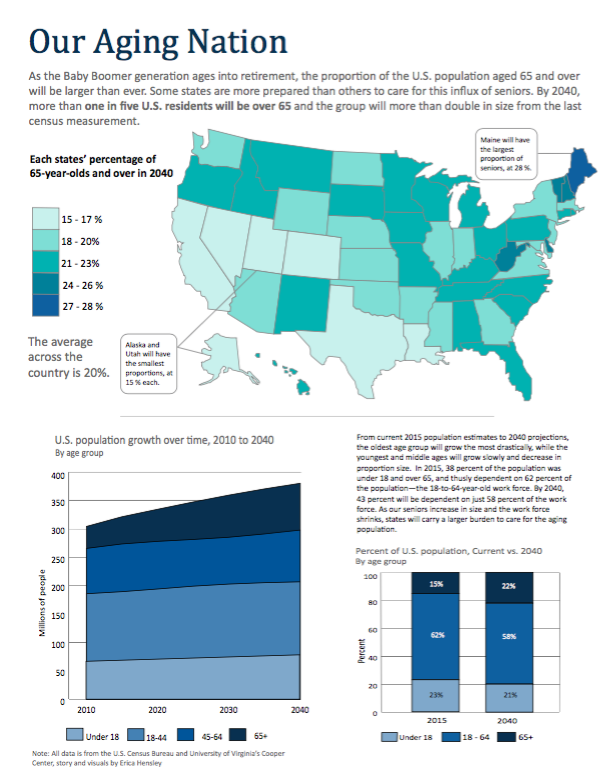

The geriatrician shortage is not unique to Athens, to Georgia, or to the United States. There are fewer than 7,500 board-certified geriatricians nationwide — about 2,000 seniors for every geriatrician — according to the American Geriatrics Society. This ratio is more than double of what one doctor reasonably can handle, the society says, and doesn’t include the two-thirds of other people over 65 who do not need specialized care — not yet, anyway.

About 13,000 additional geriatricians are needed to meet the current demand for care, according to estimates. Moreover, as the boomer generation ages, the geriatrician workforce will need to grow by 1,500 annually for the next 15 years to satisfy the nation’s need for senior care by 2030.

In Georgia, about 19 percent of the state’s population will be over 65 by then — hovering around 2 million — calling for triple the current number of geriatricians.

Athens-area residents may be better off than some Georgians because they have access to St. Mary’s Hospital and Piedmont Athens Regional. As rural hospitals continue to shutter, Athens is set to play an important role in preparing young doctors to care for elders.